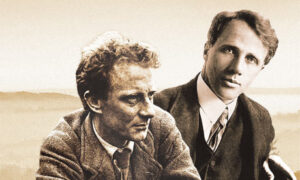

Edward Thomas, Robert Frost and the road to war

When Thomas and Frost met in London in 1913, neither had yet made his name as a poet. They became close, and each was vital to the other’s success. But then Frost wrote ‘The Road Not Taken’, which was to drive Thomas off to war

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost … so close was their friendship that they had planned to live side by side in America. Photographs: Cotswolds Photo Library/Alamy. Digital Image by David McCoy for GNM Imaging

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost were sitting on an orchard stile near Little Iddens, Frost’s cottage in Gloucestershire, in 1914, when word arrived that Britain had declared war on Germany. The two men wondered idly whether they might be able to hear the guns from their corner of the county. They had no idea of the way in which this war would come between them. In six months, Frost would flee England for the safety of New Hampshire; he would take Thomas’s son with him in the expectation that the rest of the Thomas family would follow.

So close was the friendship that had developed between them that Thomas and Frost planned to live side by side in America, writing, teaching, farming. But Thomas was a man plagued by indecision, and could not readily choose between a life with Frost and the pull of the fighting in France. War seemed such an unlikely outcome for him. He was an anti-nationalist, who despised the jingoism and racism that the press was stoking; he refused to hate Germans or grow “hot” with patriotic love for Englishmen, and once said that his real countrymen were the birds. But this friendship – the most important of either man’s life – would falter at a key moment, and Thomas would go to war.

Thomas was 36 that summer of 1914, Frost was 40; neither man had yet made his name as a poet. Thomas had published two dozen prose books and written almost 2,000 reviews, but he had still to write his first poem. He worked exhaustedly, hurriedly, “burning my candle at 3 ends”, he told Frost, to meet the deadlines of London’s literary editors; he felt convinced that he amounted to little more than a hack. He was crippled by a depression that had afflicted him since university. His moods had become so desperate that on the day he was introduced to Frost, he carried in his pocket a purchase that he ominously referred to as his “Saviour”: probably poison, possibly a pistol, but certainly something with which he intended to harm himself.

At such periods of despair Thomas would lash out at his family, humiliating his wife, Helen, and provoking his three children to tears. He despised himself for the pain he inflicted on them and would leave home, sometimes for months on end, to spare them further agony. “Our life together never was, as it were, on the level – ” Helen reflected candidly after his death, “it was either great heights or great depths.” But Edward’s heights were not Helen’s, and his depths were altogether deeper. He sought professional help at a time when little was available, and was fortunate to come under the supervision of a pioneering young doctor, a future pupil of Carl Jung’s, who attempted to treat him using a talking cure. The clinical sessions had been progressing for a year when Thomas abruptly turned his back on them. Yet he continued to look to others to help wrench him from his despondency, believing that a rescuer would one day emerge. “I feel sure that my salvation depends on a person,” he once prophesised, “and that person cannot be Helen because she has come to resemble me too much.” Such a figure would indeed arrive to help him in his distress – Robert Frost.

Frost had moved his family to England in 1912 in a bid to relaunch a stalled literary career. Then in his late 30s and a father of four, he had managed to publish only a handful of poems in America’s literary magazines. He had not been sure whether to relocate his family to London or to Vancouver, so while his wife did the ironing, he had taken a nickel from his pocket and flipped it. It was heads, which meant London, and two weeks later the entire family was steaming across the Atlantic.

He found a publisher in London for his poems soon enough (partly subsidised by himself), though few critics gave his work a second look. But Edward Thomas did. Where other reviewers mistook Frost’s verse as simplistic, Thomas was moved to announce his 1914 volume North of Boston as “one of the most revolutionary books of modern times”. Thomas was a fearless and influential critic, described by the Times as “the man with the keys to the Paradise of English Poetry“. He had been quick to identify the brilliance of a young American in London called Ezra Pound, and instrumental in shaping the early reception of Walter de la Mare, WH Davies and many others besides; and he was quite undaunted in taking to task the literary giants of the day if they fell below the mark, be they Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling or WB Yeats. When Thomas praised Frost, therefore, people began to take note.

North of Boston was a revolutionary work all right. In a mere 18 poems, it demonstrated the qualities that Frost and Thomas had – quite independently – come to believe were essential to the making of good verse. For both men, the engine of poetry was not rhyme or even form but rhythm, and the organ by which it communicated was the listening ear as opposed to the reading eye. For Thomas and Frost that entailed a fidelity to the phrase rather than to the metrical foot, to the rhythms of speech rather than those of poetic conventions, to what Frost liked to call “cadence”. If you have ever listened to voices through a closed door, Frost reasoned, you will have noticed how it can be possible to understand the general meaning of a conversation even when the specific words are muffled. This is because the tones and sentences with which we speak are coded with sonic meaning, a “sound of sense”. It is through this sense, unlocked by the rhythms of the speaking voice, that poetry communicates most profoundly: “A man will not easily write better than he speaks when some matter has touched him deeply,” Thomas wrote.

Neither Frost nor Thomas claimed to be the first to think about poetry this way, but their views certainly set them apart from their contemporaries, who were in furious competition in the charged atmosphere of the years before the war. Strikers, unionists, suffragettes, Irish republicans and the unemployed were just some of the rebellious groups that England strove to tame in 1914, and might very well have failed to suppress had war not broken out. The young poets emerging at the same time were, in their own way, also in revolt against the decrepitude of Victorian Britain. The centre of their activities was the newly opened Poetry Bookshop in Bloomsbury, from where two rival anthologies were produced: the manicured but popular Georgian Poetry, compiled by the secretary to the first lord of the Admiralty, Edward Marsh, and the radically experimental Des Imagistes, edited by Ezra Pound. It took no time at all for these parties to quarrel: so exasperating and offensive did Pound find Georgian verse that he challenged one of its protagonists to a duel.

Thomas and Frost ploughed their own furrow. Whenever Thomas visited Frost in 1914, they would walk out together on the fields of Gloucestershire; wherever they walked, they moved in an instinctive sympathy. Frost called these their “talks–walking”: and in them, their conversations ranged over marriage and friendship, wildlife, poetry and the war. Sometimes there was no talk and a silence gathered about them; but often at a gate or stile it started up again or was prompted by the meeting of a stranger in the lanes – a word or two and they were off again. They went without a map, setting their course by the sun or by the distant arc of May Hill crowning the view to the south; at dusk, the towering elms and Lombardy poplars or the light of a part-glimpsed cottage saw them home.

“He gave me standing as a poet,” Frost said of Thomas, “he more than anyone else.” But Frost would more than repay the favour that summer, recognising an innate poetry within Thomas’s prose writings, and imploring his friend to look back at his topographic books and “write them in verse form in exactly the same cadence”. Thomas would do just that, and with his friend’s encouragement, started down a path that would take him away from the “hack” work from which he earned his living. Jack Haines was a poet and solicitor living nearby in 1914 and was one of the few people who witnessed the transition at first hand. “It was towards the end of this same year that Thomas first began to write poetry himself,” Haines recorded, “and he did so certainly on the indirect, and I believe on the direct, suggestion of Frost, who thought that verse might prove that perfect mode of self-expression which Thomas had perhaps never previously found.”

The poems came quickly, “in a hurry and a whirl”: 75 in the first six months alone. He revised very little, explaining that the poetry neither asked for nor received much correction on paper. Often he went back to his prose to find his poem. Sometimes his source was a notebook that he kept on his walks, at other times his published books; and though the gap between his initial notes and a verse draft could be many months, once he began on the poem itself he usually completed it in a single day.

But poetry was not the only thing waking in Thomas in those summer months as the war began. Late in August, walking with Frost through the afternoon into the night, Thomas jotted in his notebook:

a sky of dark rough horizontal masses in N.W. with a 1/3 moon bright and almost orange low down clear of cloud and I thought of men east-ward seeing it at the same moment. It seems foolish to have loved England up to now without knowing it could perhaps be ravaged and I could and perhaps would do nothing to prevent it.

The war was three weeks old, and for the first time Thomas had imagined his countrymen fighting abroad, under the same moon as he. He was indifferent to the politics of the conflict, but he had begun to weigh up the worth of the land beneath his feet and the way of life that it supported. What would he do, if called on, to protect it, he asked himself. Would he do anything at all?

For a year, Thomas would question himself this way. It would take two incidents with Frost to help him to find his answer.

In late November 1914, Thomas and Frost were strolling in the woods behind Frost’s cottage when they were intercepted by the local gamekeeper, who challenged their presence and told the men bluntly to clear out. As a resident, Frost believed he was entitled to roam wherever he wished, and he told the keeper as much. The keeper was unimpressed and some sharp words were exchanged, and when the poets emerged on to the road they were challenged once more. Tempers flared and the keeper called Frost “a damned cottager” before raising his shotgun at the two men. Incensed, Frost was on the verge of striking the man, but hesitated when he saw Thomas back off. Heated words continued to be had, with the adversaries goading each other before then finally parting, the poets talking heatedly of the incident as they walked.

Thomas said that the keeper’s aggression was unacceptable and that something should be done about it. Frost’s ire peaked as he listened to Thomas: something would indeed be done and done right now, and if Thomas wanted to follow him he could see it being done. The men turned back, Frost angrily, Thomas hesitantly, but the gamekeeper was no longer on the road. His temper wild, Frost insisted on tracking the man down, which they did, to a small cottage at the edge of a coppice. Frost beat on the door, and left the startled keeper in no doubt as to what would befall him were he ever to threaten him again or bar access to the preserve. Frost repeated his warning for good measure, turned on his heels and prepared to leave. What happened next would be a defining moment in Frost and Thomas’s friendship, and would plague Thomas to his dying days.

The keeper, recovering his wits, reached above the door for his shotgun and came outside, this time heading straight for Thomas who, until then, had not been his primary target. The gun was raised again; instinctively Thomas backed off once more, and the gamekeeper forced the men off his property and back on to the path, where they retreated under the keeper’s watchful aim.

Frost contented himself with the thought that he had given a good account of himself; but not Thomas, who wished that his mettle had not been tested in the presence of his friend. He felt sure that he had shown himself to be cowardly and suspected Frost of thinking the same. Not once but twice had he failed to hold his ground, while his friend had no difficulty standing his. His courage had been found wanting, at a time when friends such as Rupert Brooke had found it in themselves to face genuine danger overseas.

The encounter would leave Thomas haunted, to relive the moment again and again. In his verse and in his letters to Frost – in the week when he left for France, even in the week of his death – he recalled the feeling of fear and cowardice he had experienced in that stand-off with the gamekeeper. He felt mocked by events and possibly even by the most important friend he had ever made, and he vowed that he would never again let himself be faced down. When the moment came he would hold his nerve and face the gunmen. “That’s why he went to war,” said Frost later.

But it would take one further episode in Thomas’s friendship with Frost to push him to war; and it would turn on a work of Frost’s that has becomeAmerica’s best-loved poem.

In the early summer of 1915, six months after the row with the gamekeeper, Thomas had still to take his fateful decision to enlist. Zeppelins had brought the war emphatically to London, but Thomas’s eyes were on New Hampshire, to where Frost had returned earlier that year. Thomas prepared his mother for the news that he might emigrate, and told Frost he seemed certain to join him: “I am thinking about America as my only chance (apart from Paradise).” But Thomas’s prevarication got the better of him once more, and though conscription had yet to be introduced, he told Frost of the equal pull of the war in France. “Frankly I do not want to go,” he said of the fighting, “but hardly a day passes without my thinking I should. With no call, the problem is endless.”

But the problem was not endless as Thomas thought, for a poem of Frost’s had arrived by post that would dramatically force Thomas’s hand: a poem called “Two Roads”, soon to be rechristened “The Road Not Taken”. It finished:

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I –

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Noble, charismatic, wise: in the years since its composition, “The Road Not Taken” has been understood by some as an emblem of individual choice and self-reliance, a moral tale in which the traveller takes responsibility for – and so effects – his own destiny. But it was never intended to be read in this way by Frost, who was well aware of the playful ironies contained within it, and would warn audiences: “You have to be careful of that one; it’s a tricky poem – very tricky.”

Frost knew that reading the poem as a straight morality tale ought to pose a number of difficulties. For one: how can we evaluate the outcome of the road not taken? For another: had the poet chosen the road more travelled by then that, logically, could also have made all the difference. And in case the subtlety was missed, Frost set traps in the poem intended to explode a more earnest reading. The two paths, he wrote, had been worn “really about the same”, and “equally lay / In leaves no step had trodden black”, showing the reader that neither road was more or less travelled, and that choices may in some sense be equal.

But the poem carried a more personal message. Many were the walks when Thomas would guide Frost on the promise of rare wild flowers or birds’ eggs, only to end in self-reproach when the path he chose revealed no such wonders. Amused at Thomas’s inability to satisfy himself, Frost chided him, “No matter which road you take, you’ll always sigh, and wish you’d taken another.”

To Thomas, it was not the least bit funny. It pricked at his confidence, at his sense of his own fraudulence, reminding him he was neither a true writer nor a true naturalist, cowardly in his lack of direction. And now the one man who understood his indecisiveness the most astutely – in particular, towards the war – appeared to be mocking him for it.

Thomas responded angrily. He did not subscribe to models of self-determination, or the belief that the spirit could triumph over adversity; some things seemed to him ingrained, inevitable. How free-spirited his friend seemed in comparison. This American who sailed for England on a long-shot, knowing no one and without a place to go, rode his literary fortunes and won his prize, then set sail again to make himself a new home. None of this was Thomas. “It isn’t in me,” he pleaded.

Frost insisted that Thomas was overreacting, and told his friend that he had failed to see that “the sigh was a mock sigh, hypocritical for the fun of the thing”. But Thomas saw no such fun, and said so bluntly, adding that he doubted anyone would see the fun of the thing without Frost to guide them personally. Frost, in fact, had already discovered as much on reading the poem before a college audience, where it was “taken pretty seriously”, he admitted, despite “doing my best to make it obvious by my manner that I was fooling . . . Mea culpa.”

“The Road Not Taken” did not send Thomas to war, but it was the last and pivotal moment in a sequence of events that had brought him to an irreversible decision. He broke the news to Frost. “Last week I had screwed myself up to the point of believing I should come out to America & lecture if anyone wanted me to. But I have altered my mind. I am going to enlist on Wednesday if the doctor will pass me.”

In walking with Frost, he had written of the urgent need to protect – and if necessary, to fight for – the life and the landscape around him. “Something, I felt, had to be done before I could look again composedly at English landscape,” he explained, though he had struggled for some time to see what it was that might be done. Finally, he understood. Thomas was passed fit by the doctor, and the same week, in July 1915, he sat down to lunch with a friend and informed her that he had enlisted in the Artists Rifles, and that he was glad; he did not know why, but he was glad.

“I had known that the struggle going on in his spirit would end like this,” his wife wrote.

Thomas brought a unique eye to the English landscape at a moment when it was facing irreversible change. His work seems distinctly modern in its recognition of the interdependence of human beings and the natural world, more closely attuned to our own ecological age than that of the first world war.

Though few of his poems were published in his lifetime, his admirers have been many: WH Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, Dylan Thomas, Philip Larkin, Ted Hughes, Andrew Motion and Michael Longley among them. But perhaps no poet ever valued him more highly than Robert Frost: “We were greater friends than almost any two ever were practising the same art,” he remarked. A war, a gamekeeper and a road not taken came between them, but by then they had altered one another’s lives irrevocably. Thomas pulled his friend’s work from obscurity into a clearing, from which the American would go on to sell a million poetry books in his lifetime. Frost, in turn, released the poet within Thomas, and would even find a publisher for his verse in the United States. That book would carry a dedication that Thomas had scribbled on the eve of sailing for France: “To Robert Frost”. Frost responded in kind, writing: “Edward Thomas was the only brother I ever had.”

At twilight when walking, or at the parting of ways with a friend, Thomas could feel great sadness that his journey must come to an end:

Things will happen which will trample and pierce, but I shall go on, something that is here and there like the wind, something unconquerable, something not to be separated from the dark earth and the light sky, a strong citizen of infinity and eternity.

He was killed on the first day of the battle of Arras, Easter 1917; he had survived little more than two months in France. Yet his personal war was never with a military opponent: it had been with his ravaging depression and with his struggle to find a literary expression through poetry that was worthy of his talents. And on the latter, at least, he won his battle.

Read my new memoir: Rosaries, Reading, Secrets: A Catholic Childhood in India (US) or UK.

Connect on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/anitamathiaswriter/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/anita.mathias/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AnitaMathias1

My book of essays: Wandering Between Two Worlds (US) or UK