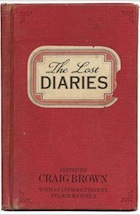

Craig Brown: The Lost Diaries

How do you out-snob Virginia Woolf, out-raunch DH Lawrence and out-rant Germaine Greer? Craig Brown explains the parodist’s art

Some authors appreciate being parodied . . .

In 1912, Max Beerbohm published “The Mote in the Middle Distance”, his parody of Henry James. It begins: “It was with a sense of a, for him, very memorable something that he peered now into the immediate future, and tried, not without compunction, to take that period up where he had, prospectively left it. But just where the deuce had he left it?”

Beerbohm was understandably anxious about James’s reaction. As well he might, since it so slyly captures James’s oblique, elliptical style, a style compared by HG Wells to “a magnificent but painful hippopotamus resolved at any cost, even at the cost of its dignity, upon picking up a pea which has got into a corner of its den”.

But after dinner with Henry James, Edmund Gosse was able to reassure Beerbohm that James “desired me to let you know at once that no one can have read it with more wonder and delight than he”.

Later that year, James and Beerbohm were guests at the same party. When an admirer asked James his opinion on something-or-other, James pointed across the room to Beerbohm and said: “Ask that young man. He is in full possession of my innermost thoughts.”

On my own, more modest level, the roster of those who have enjoyed my parodies of them is wholly unpredictable. Marianne Faithfull sent me a thankyou letter, as did Roy Jenkins (his widow found it on his desk after his death, and kindly passed it on to me). WG Sebald also enjoyed my parody of his trip to the seaside (“High above me in the air, the seagull continued upon its vacuous and erratic journey through a sky still glowering in fury at the ceaseless intrusion of the crazed sun”), though, again, I only discovered this after he had died, having spent one shared lunch-party sheepishly trying to avoid him.

. . . while others do not.

Seven or eight years ago, I was at a large party consisting of perhaps a couple of hundred people. At one point, I glanced across the sea of heads to the other side of the room, only to be confronted by the terrifying sight of Harold Pinter staring back at me, his face set in a gargoylish grimace, each thumb stuck to the side of his head while his fingers waggled about in the traditional schoolboy gesture of derision.

It was a scary sight, at one and the same time daft and threatening, not to mention weirdly psychic (how did he know that I would glance over at that moment, or had he been pulling faces for some time, on the off-chance?)

The next day, I heard that he had said to our hostess: “Is that who I think it is?” “Yes. Are you going to punch him?” she said, to which he replied, “I wouldn’t dirty my fists.”

Parody is a remarkably libel-proof mode of abuse.

If you call someone a liar or a crook in print, the next day you are likely to be showered with letters from Messrs Sue, Grabbit and Runne. If, on the other hand, you demonstrate what you are getting at in parodic form, you will probably get off scot-free. Parody is read between the lines. It is as though lawyers, denied humour’s x-ray specs, are unable to see what everyone else can see. A parody gets at the truth by parading truth’s opposite: the reader is left to put two and two together. So as the former royal butler Paul Burrell fondly reminisces about his life at Buckingham Palace, he simultaneously by-passes legal objections:

“Her Majesty was a lovely lady. She thought the world of me. She would often call by on her nights off. I got used to that tell-tale knock on the door. She would drum out the opening bars of the National Anthem with her clenched fist. That way, I knew it was her. I’d open the door, and there she’d be, dressed in casual clothes – a pair of designer denims and a favourite kaftan. Often she’d let her hair hang down, so it flowed over her creamy shoulders. It gave her the more relaxed and carefree look she had always craved. ‘You know, you should keep it like that, ma’am – you look truly fabulous!’ I once ventured, but she looked downcast. ‘My public would never accept me like that, Paul!’ she said. ‘They like me with it up!’ At that point, she got out her guitar and sang me one of my all-time favourite songs – Ralph McTell’s Streets of London. It was a very private moment.”

A parody can be both unfair and funny or fair and funny. But it should never be either unfunny and fair, or unfair and unfunny.

Edward Lear was, I think, one of the great Victorian originals, but at the same time I consider this parody of his nonsense verse by John Clarke, reproduced in John Gross’s recent Oxford Book of Parodies, is indisputably accurate:

There was an old man with a beard,

A funny old man with a beard

He had a big beard

A great big old beard

That amusing old man with a beard.

Often it is the addition of a single, unassuming word that jolts the humdrum into the humorous. In the above case, I think it is the word “amusing”.

Many funny writers don’t have a sense of humour.

Instead of laughing at someone else’s joke, they tend to say: “That’s funny,” and then squirrel the joke away, ready for a crafty respray at some time in the future.

Just as most fishermen don’t like the taste of fish, many humorists don’t have a sense of humour. Jonathan Swift claimed to have only ever laughed twice in his entire life; Alexander Pope couldn’t remember ever having laughed. Like many professional humorists, Keith Waterhouse would never tell jokes in company, saying it was the closest thing to throwing gold coins down the drain.

To make some parodies more credible, the parodist must first make their originals less ridiculous.

I remember reading this passage by Germaine Greer against, of all things, teddy bears, in the Guardian a year or two ago, and feeling bewildered as to how I might parody it:

“Teddies and bunnies are taken into exams and sat on the desks, as if to be without them for three hours would induce hysteria and fainting spells. Soft toys are left along with the flowers at the scenes of fatalities. Wherever they are, they are truly hideous, beyond kitsch. By making our children fall in love with such ugliness, we are preparing them for a life without taste.

. . . I have certainly seen a two-year-old humping her teddy bear. If we persist in decoying children away from demanding relationships with humans by providing them with undemanding animal fetish objects, we should not be surprised if they end up like Big Brother housemate Jonty Stern, who, at the age of 36, is still a virgin.”

It struck me then, and still strikes me now, as a perfect example of self-parody, a condensed lampoon of all that writer’s worst tendencies towards needless iconoclasm, exasperation, sensationalism, exaggeration and the hoovering up of current news items: like so many opinionistas, Greer can never see the wrong end of a stick without trying to grab it with both hands.

The trouble for the parodist, though, is that Greer leaves no room for improvement: it’s perfect as it is. The same goes for Edwina Currie’s diaries, Tracey Emin’s meanderings, John Prescott’s splutterings and Harold Pinter’s poems. In my new collection of parodies, The Lost Diaries, which is arranged along the lines of a calendar, with one or two entries for each day of the year, I have placed a number of such pieces under April 1st, with the asterisked caution to the reader that they are, alas, real.

Every child is born a parodist.

Children learn to speak by parodying their parents. When grown-ups roll their eyes in amusement at children’s remarks and exclaim “The things they come up with!” they are in fact laughing at a skewed version of themselves. The process continues as life goes on: most political speeches, for instance, are parodies of earlier political speeches. President Obama’s oratory has the same rhythms as Dr Martin Luther King’s, and it sometimes seems that every speaker at a British political party conference has come as Winston Churchill.

The more accurate the parody, the more likely it is to be confused with the real thing.

Terence Blacker and the late William Donaldson, aka Henry Root, once published a spoof of tabloid journalism called “101 Things You Didn’t Know About the Royal Love-Birds” by “Talbot Church, The Man the Royals Trust”, to tie in with the wedding of Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson. It revealed that the Ferguson family motto is “Full steam ahead” and included items such as “Fergie wore braces on her teeth until she was 16. When these were removed she blossomed overnight into the flame-haired beauty with an hour-glass figure we see today – but their removal left her with a slight speech impediment and she was unable to say the word ‘solicitor’ until she was 21.”

It was such an accurate parody of tabloid journalism that it was lifted without a by-your-leave by the Sun, who did not realise it was a spoof, and later by the American biographer Kitty Kelley, who inserted Talbot Church jokes into her book about the royal family, presumably in the belief they were hard facts.

To appreciate parody, you must be capable of holding two contradictory ideas in your head simultaneously.

For some years, I wrote the parodic Bel Littlejohn column in the Guardian. It seemed to me that only about half the readers twigged that it was a spoof; the others, whether they liked her or loathed her, believed Bel to be the real thing. In 1997, she was given her own entry in Who’s Who (as was my spoof Spectator columnist Wallace Arnold). After writing a Why-Oh-Why piece on the need for correct grammar, Wallace Arnold received a letter from the chairman of the government’s new Good English Campaign, Sir Trevor McDonald, asking him to join them.

I was reliably informed that the historian Eric Hobsbawm once told someone that he had known Bel in the 70s, but that her writing had gone off a bit. When she mentioned in one column that she had been a student at Leeds University with Jack Straw in the 1960s, she received a letter inviting her to join the Leeds University Old Alumni Association. She once wrote a piece in support of the progressive school Summerhill, which was threatened with closure. “Okay so maybe the kids can’t read and write – but when’s that ever been the point of school? Last year, two of those so-called ‘uneducated kids achieved a Grade C, thank you very much, and an under-matron gained her black belt in karate . . . The school budgerigar, Tarantino, won the underwater swimming competition, for which he was awarded a posthumous trophy.”

A couple of days later, I received a letter from the chair of the Centre for Self-Managed Learning. “Absolutely spot-on – wonderful . . .” he wrote. “We are 100% with the sentiments in your article and are keen to do something practical to address the issue.” I realised with a start that he was not being ironic.

But it was never my intention to fool people. What would be the point? A parody only works if, with one side of his brain, the reader knows that it is a joke but with the other side is able to entertain the idea that it is real. To someone who thought she was real, Dame Edna Everage would just be a bossy, self-promoting Australian vulgarian. To someone who could only see her as an artificial construct, she would just be a man dressed up as a woman saying deliberately provocative things. For the joke to emerge, the brain must be capable of holding both ideas at once. The same is true of all parody and impersonation, and perhaps of all art: those who look at a painting of apples by Cézanne and see a real bunch of apples are as blind to the art within as those who can see only strokes of paint, representing nothing.

Parody represents a collaboration, however unwilling, between the parodist and his victim.

It is sometimes said that the best parodies are affectionate. I don’t think this is always true. Max Beerbohm had a deep loathing of Rudyard Kipling, but his Kipling parody (“An’ it’s trunch trunch truncheon does the trick”) is a thing of joy. The Mary Ann Bighead column in Private Eye is manifestly not enamoured of its real-life target, but remains sublimely funny.

On the other hand, parody is a pas-de-deux, in that the parodist must inhabit the language and speech-rhythms of the parodied while subverting them for his own ends. Thus a certain strange empathy is called for, no matter how cold-hearted.

There is no place with so few good books as the parodist’s library.

Among the books on my shelves are Barbara Cartland’s Love at the Helm; The Crossroads Cookbook; My Tune by Simon Bates; all four volumes of Katie Price’s autobiography; The Duchess of York’s Budgie: The Little Helicopter; the autobiographies of Edward Du Cann, Anthea Turner, Norman Fowler, Tim Rice, George Carey, Max Clifford and Peter Purves; Reg Kray’s Thoughts, Philosophy and Poetry; The Wit of Prince Philip; Enoch Powell’s Collected Poems; My Friends’ Secrets by Joan Collins; Inspired and Outspoken: The Collected Speeches of Ann Widdecombe; and Doris Stokes’s Voices of Love.

They are all heavily annotated, with the most gruesome passages all dutifully underlined. For instance, my copy of Prezza: The Autobiography of John Prescott has multiple markings beneath the regurgitation passages, and my copy of Tony Blair’s autobiography carries heavy underlinings beneath his night of passion with Cherie. In Simon Heffer’s new book, horribly titled Strictly English: The Correct Way to Write . . . and Why it Matters, I have put a double ring around “I once got a job by finding 24 mistakes in a piece of prose in which I had been told I would find 20, and which had been given to me as part of a test during an interview: this was because the person who had set the test, good though his English was, did not know about gerunds.” A double ring tends to mean that a passage can go straight into my parody of it, completely unaltered.

It is the task of the regular writer to pick exactly the right word. The task of the parodist is different: he must pick exactly the wrong word.

“To Chatsworth. Poky.” This was my Woodrow Wyatt diary; at three words, it is probably the shortest parody I have written.

. . . But occasionally the two aims coincide.

“Suicide mass-murder is more than terrorism: it is horrorism,” wrote Martin Amis in The Second Plane.

Topical humour lasts only as long as its victims . . .

Like a particularly giggly form of parasite, parody can expect to live only as long as its host. “Who’s Nancy dell’Olio?” a teenager asked me the other day, while browsing through the The Lost Diaries. For a second, I struggled to remember. “The ex-girlfriend of Sven-Goran Eriksson!” I explained. “Who’s Sven-Goran Eriksson?” came the reply.

The book is already 400 pages long, but in 50 years time, the book will require a further 400 pages of explanatory notes by a learned academic. Take the “F”‘s, for instance: Faithfull, Marianne, Fayed, Mohamed; Feltz, Vanessa; Fergusson, Major Ronald; Fermoy, Ruth, Lady”. I suspect Review readers may already be struggling. I can give them just the briefest rest-stop – “Flaubert, Gustave” – before plunging back in with “Fletcher, Cyril; Follett, Barbara; Follett, Ken; Ford, Tom and Fowler, Sir Norman” et cetera.

Like so many things these days, the book is vulnerable to built-in obsolescence – particularly as I have a perverse interest in already-ghostly figures such as Cyril Fletcher and Ruth, Lady Fermoy (whose name, for some reason, always makes me titter). Her full index-entry is “Fermoy, Ruth, Lady: rejoices at the Queen Mother breaking wind 112 (and footnote); begs like dog 182; plays ‘Any Old Iron’ 212-13.” Needless to say, all those jokes are based around the idea of their unlikelihood – but who, in a few years time, will be able to recollect that Ruth, Lady Fermoy would have taken a fierce pride in not breaking wind, or begging like a dog, or leading cockney sing-songs?

Among my Fs, the only entry with an odds-on hope of being known in 100 years time is Lucian Freud, who pops up in Queen Elizabeth II’s diary when he is painting her portrait (“Freud: not a name you hear very often,” she reflects). His closest runner is Lady Antonia Fraser. “Orders Château d’Yquem on behalf of the sugar plantation workers of East Timor; tips the Kinnocks; quizzes Castro about Joanna Trollope; finds Paris ‘very French'”, reads her entry: yet more explanatory toil for our poor, exhausted footnoter.

. . . though there are one or two who get away, and long outlive their host.

Some of the most notable classics of English humour – Diary of a Nobody, Three Men in a Boat, parts of Alice in Wonderland, Cold Comfort Farm – began life as parodies of works that are now forgotten. In the reverse of the normal process, they now ensure their victims a ghostly kind of immortality.

There is no avoiding parody . . .

The greatest writers may also be the most parodiable, as their style and vision are necessarily singular. Alan Bennett, John Updike, Philip Roth are all exceptional writers, and it is this idiosyncrasy that makes them susceptible to parody. God Himself is peculiarly easy to ape: I remember sailing through the Old Testament section of my Theology A-level by making up all the rumbling, hoity-toity and frequently bad-tempered quotes from God and his prophets Isaiah, Ezekiel and Hosea. It was so much easier than remembering the real ones.

In the introduction to his endlessly enjoyable Oxford Book of Parodies, John Gross explains the way in which parodists often rejoice in their subjects. “They are not telling us that we should not write like Robert Browning (or George Crabbe or Henry James or Muriel Spark), still less that Browning should not write like Browning – that he should choose to apprehend the universe in this one peculiar fashion. And how gratifying that he should keep it up – that he can always be relied on to be Browningesque.”

. . . Unless you are a bore. But even bores can be parodied, just as long as they are boring enough.

The only way to be truly beyond parody is to be run-of-the-mill. But you should be careful to be just interesting enough, as excessive tedium becomes a joke in itself. When I read Margaret Drabble’s memoir The Pattern in the Carpet I realised that I had struck gold. One sentence, about her tiresome “dotty” aunt (could editors please declare a moratorium on dotty aunts?), reads: “I maintain (though she queried this) that it was I who usefully introduced her to scampi and chips, at an excellent but now defunct hostelry overlooking the Bristol Channel at Linton.” Indeed, I kicked off my parody with it, and then added some more, for good measure:

“I maintain (though she might, in truth, query this) that it was I who usefully introduced my Aunt Phyl to scampi and chips, at an excellent but now defunct castellated hostelry overlooking the Bristol Channel at Linton in 1973. Or was it 1974? Conceivably (and here I am, metaphorically speaking, sticking my neck out) it was 1972, or even 1971, though if it was 1971, then it might not have been the castellated hostelry that we ate in, as a useful visit to my local library yesterday afternoon between 3.30pm and 4.23pm confirmed me in my suspicion that the hostelry in question was in fact closed for the greater part of 1971, owing to a refurbishment programme. In that case, and if it really was 1971, which, frankly, seems increasingly unlikely given the other dates available, then it is within the realms of possibility that we ate at another hostelry entirely, possibly one overlooking the North Sea, and, if so, it is equally possible that we feasted not on scampi and chips but on shepherd’s pie. Did we also consume a side-order of vegetables? Memory is, I have found, a fickle servant, so I am unable to recall whether, on this occasion, we indulged in a side-order of vegetables, if we were there at all.”

Extracts from The Lost Diaries:

Virginia Woolf

May 7th

Am I merely snobbish in thinking that the lower classes have no aptitude or instinct for great literature or indeed literature of any kind? This morning I went into the kitchen & found Nelly sitting down reading a cookery book. How will you ever improve your lower-class mind if you spend your days simply reading receipts? I asked her, kindly.

Her reply was intolerable. She said that she was reading her cookery book for my benefit & if I did not want her to read it then fine, she would gladly seek employment elsewhere among people who would appreciate her & would not seek to undermine her every move, & do not call me lower class when I am lower middle class than you very much – and you are not much higher if truth be told.

I could take no more & so lashed out at her with a tea-towel, flipping it again & again in her odious fat face screaming at her, You have made me the most miserable person in the whole of Sussex and I shall not forgive you for it.

Unbeknownst to me, Nelly was carrying her own tea-towel about her unduly bulging person as plump as a ptarmigan & as I paused to regain my breath she whipped it out from its hiding place & struck me with it once twice three no four times in quick & brutal succession. She persists; brutally tramples. I asked myself: am I forever doomed to let every worry, spite, irritation & obsession scratch and claw at my brain?

It was at this point that I recalled the disciplines taught so fortuitously at the unarmed combat course at Rodmell village hall in which Vita & I enrolled last year. I set my fingers in a V and, leaping up from the kitchen floor, I poked them into Nelly’s ill-formed, damp & porcine eyes. She howled her lower-class howl & fell to the ground, begging for a mercy which, in my present state, I had little inclination to offer. I remarked upon how underbred, illiterate, insistent, raw & ultimately nauseating she was before retiring from the room to my bed, therewith to restore myself with a little George Eliot.

DH Lawrence,

Letter to Lady Ottoline Morrell

November 29th, 1922

Dear Lady Ottoline,

I cannot tell you how thoroughly we both enjoyed staying with you last weekend. Everything was so perfect – the scintillating conversation, the delicious food, the excellent wine, and all miraculously brought together to perfection by the finest hostess in the country!

By the way, I do hope I didn’t cause any undue offence at dinner with your guests on Saturday evening when, just as that lovely soup was being served, I tore off my trousers, pulled out my aroused member and began to chase your buxom serving wench around the dining-room table.

I noticed that your first thought was that the tomato soup in the wench’s great bowl was being tossed hither and thither over your well-dressed guests. How typical of you and your feeble servility towards the pathetic silliness of propriety that you should care more for the laundering of clothes – those absurd chains that keep man from his true self – than for the sex-flow that keeps man alive and is the only honest expression of animal energy that exists on this miserable globe.

And when I eventually caught up with her, and managed to grapple her to the ground, and was struggling to grasp her bountiful delights within my needy palms – then you implored me to forbear, you rang your bell and insisted in your cheap and degraded voice that there was ‘a time and a place for everything’.

Do you realise what a loathsome thing you are? You make me ill. I wanted to light a flame, to warm my body against the heat of a real woman’s naked form, to worship the sun-god of the sex-flow – and all you could think of to do was beg me hysterically to desist! You and your sort have a disgusting attitude towards sex, a disgusting desire to stop it and insult it. You are like a worm cut in half, with one half discarded in a bin while the other half wriggles around in a kind of grey hell.

Nevertheless, the main course was absolutely delicious, and I know that everyone also thoroughly enjoyed the pudding. And the rest of the weekend was every bit as heavenly! You were really extremely kind to entertain us all so extravagantly. Once again, thank you so much for a really wonderful weekend.

Yours ever,

David

Read my new memoir: Rosaries, Reading, Secrets: A Catholic Childhood in India (US) or UK.

Connect on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/anitamathiaswriter/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/anita.mathias/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AnitaMathias1

My book of essays: Wandering Between Two Worlds (US) or UK